As I have written a number of times already, including in my previous post, I still don’t get (i) why cryptocurrencies create better market conditions for building ventures than good old fashioned money, and (ii) why tokenization – instead of just giving investors and workers plain old money – is the only viable path to building a successful business in the digital era. And when the answer comes in the form of a libertarian soundbite about democratization of money, the burden of regulations or the end of intermediation, I am convinced the speaker knows nothing about history, technology or business. The answer has sham (or gullible) written all over it.

That, of course, doesn’t mean that I don’t believe in distributed ledgers (aka Blockchain technologies) as interesting solutions for solving some important transactional inefficiencies. It’s the whole obsession with tokenization and refusing to use real money that baffles me.

With this in mind, I was very encouraged by a series of Nouriel Roubini tweets over the weekend where Roubini – who made a public name for himself by being one of the few, brave souls to openly predict the 2008 economic crash – unabashedly called out the willful blindness, ignorance and outward deception of Crypto’s most ardent supporters. For example:

I wrote a 30 page testimony that was a thoughtful critique of crypto and blockchain. And no one, not even @VitalikButerin was able to give me a rebuttal of it. Only 100s of rabid crypto barking dogs hurling insults and threats. It says a lot about the intellect of these losers https://t.co/c4eKa3wESc

— Nouriel Roubini (@Nouriel) October 12, 2018

So instead of trusting governments I need to trust an oligopoly of Chinese miners who are shady and plan to shaft me? Get real once and for all: there is NO decentralization in crypto. It is a myth. It is a system controlled by a shady oligopoly of miners in shadier countries https://t.co/OJYCTKsrJ6

— Nouriel Roubini (@Nouriel) October 14, 2018

So the cost per transaction of bitcoin is literally $60. So if I were to buy a $3 latte at Starbucks I would have to pay $63 to get it! So the myth of a “Brilliant new technology that reduces the vast fees of legacy financial systems”! turns out to be a Big Fat Lie! https://t.co/vcOGTNcu7N

— Nouriel Roubini (@Nouriel) October 14, 2018

Bitcoin is indeed an environmental disaster https://t.co/65JMcv3Do3

— Nouriel Roubini (@Nouriel) October 15, 2018

Then this morning, Roubini published this must-read article “Blockchain isn’t about democracy and decentralization – it’s about greed” where he makes all of the aforementioned arguments about the false narratives around cryptocurrencies, including:

In practice, blockchain is nothing more than a glorified spreadsheet. But it has also become the byword for a libertarian ideology that treats all governments, central banks, traditional financial institutions, and real-world currencies as evil concentrations of power that must be destroyed. Blockchain fundamentalists’ ideal world is one in which all economic activity and human interactions are subject to anarchist or libertarian decentralization. They would like the entirety of social and political life to end up on public ledgers that are supposedly “permissionless” (accessible to everyone) and “trustless” (not reliant on a credible intermediary such as a bank).

Yet far from ushering in a utopia, blockchain has given rise to a familiar form of economic hell. A few self-serving white men (there are hardly any women or minorities in the blockchain universe) pretending to be messiahs for the world’s impoverished, marginalized, and unbanked masses claim to have created billions of dollars of wealth out of nothing. But one need only consider the massive centralization of power among cryptocurrency “miners,” exchanges, developers, and wealth holders to see that blockchain is not about decentralization and democracy; it is about greed.

But he also makes an interesting observation about the non-crypto part of Blockchain as well:

Moreover, in cases where distributed-ledger technologies – so-called enterprise DLT – are actually being used, they have nothing to do with blockchain. They are private, centralized, and recorded on just a few controlled ledgers. They require permission for access, which is granted to qualified individuals. And, perhaps most important, they are based on trusted authorities that have established their credibility over time. All of which is to say, these are “blockchains” in name only.

It is telling that all “decentralized” blockchains end up being centralized, permissioned databases when they are actually put into use. As such, blockchain has not even improved upon the standard electronic spreadsheet, which was invented in 1979.

No serious institution would ever allow its transactions to be verified by an anonymous cartel operating from the shadows of the world’s authoritarian kleptocracies. So it is no surprise that whenever “blockchain” has been piloted in a traditional setting, it has either been thrown in the trash bin or turned into a private permissioned database that is nothing more than an Excel spreadsheet or a database with a misleading name.

I absolutely agree, and for the reasons he states, I actually like private blockchains. Not to change the world, but to improve processes. And if you control those spreadsheets, you are able to give your customers much more flexibility, protection and value. Works for me!

The more I hear Blockchain evangelists preach about tokenization and how cryptocurrencies will democratize technology, the more I am convinced that cryptocurrencies are one big swindle. I have already discussed this more in depth

The more I hear Blockchain evangelists preach about tokenization and how cryptocurrencies will democratize technology, the more I am convinced that cryptocurrencies are one big swindle. I have already discussed this more in depth

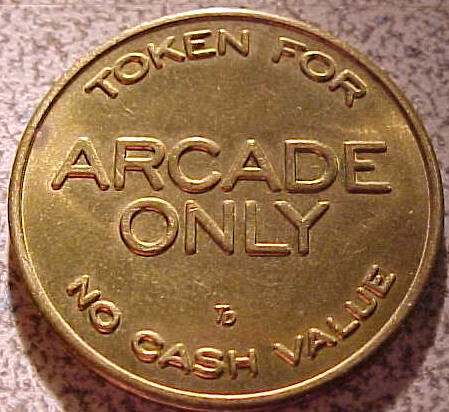

Think of cryptocurrencies as those tokens at a video arcade where in exchange for hard currency (or services), you are given tokens that can be used at the arcade. The tokens would generally have no value outside of the arcade, unless there is demand for exchanging goods, services, or other currencies for those tokens.

Think of cryptocurrencies as those tokens at a video arcade where in exchange for hard currency (or services), you are given tokens that can be used at the arcade. The tokens would generally have no value outside of the arcade, unless there is demand for exchanging goods, services, or other currencies for those tokens.

We keep hearing that governments will kill cryptocurrencies or at least regulate them to death. They fear what they cannot control (or tax). I tend to keep a more open mind.

We keep hearing that governments will kill cryptocurrencies or at least regulate them to death. They fear what they cannot control (or tax). I tend to keep a more open mind.